Josh Hendrickson has a new Substack post that discusses the implications of the US dollar’s role as an international reserve currency. This caught my eye:

When you are taught a typical model of international trade with flexible exchange rates, discussion of the balance of trade goes something like this. If a country runs persistent trade deficits, its currency will begin to depreciate. The depreciation of the currency makes foreign goods more expensive. This tends to reduce imports and push the country toward balanced trade. The basic point here is that a typical textbook argument is that flexible exchange rates adjust to the balance of trade and these adjustments tend to reduce the trade deficit and push the country towards balanced trade.

By contrast, the U.S. runs persistent trade deficits that do not self-correct. In fact, many times, the dollar appreciates while the U.S. is running trade deficits. How can we explain this phenomenon?

The reason that the U.S. is different is that the dollar is the primary currency used in global trade.

Two comments:

- The US isn’t different.

- Josh Hendrickson should get a new textbook.

Here’s the US current account as a share of GDP:

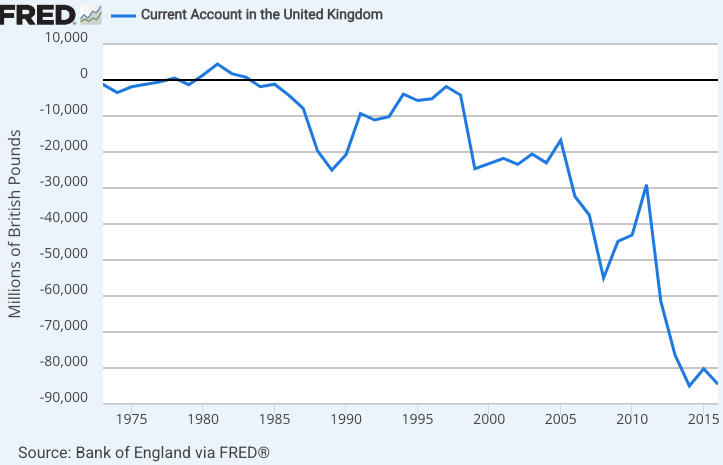

Now let’s look at Great Britain:

Unfortunately, the British FRED series ends in 2016 and is in money terms, not share of GDP. However, another source confirms the UK current account deficits have continued at roughly 3% of GDP.

And here’s New Zealand:

And here’s Australia:

In fairness, a more recent Fred series shows a brief period of surplus, before returning to deficit in 2024:

In fact, the US is fairly typical of English-speaking countries that draw a lot of immigration—it runs fairly persistent deficits. The outlier is Canada, which ran current account surpluses from 1999-2008, but even they have seen current account deficits for the past 16 years, and 52 of the past 65 years.

A current account balance merely reflects the difference between saving and investment; there’s no reason why it cannot continue indefinitely. It may be associated with excessive borrowing, especially excessive government borrowing, but that is not always the case. (Australia tends to have small budget deficits.)

The US current account deficits are probably caused by the same sort of factors that explain current account deficits in other English-speaking countries: low saving rates, highly productive capital investments and high rates of immigration. I see no evidence that the dollar’s role as a reserve currency plays much of a role, unless you believe that the New Zealand dollar is also an important reserve currency.

Hendrickson continues:

The short answer is that other countries have to be net importers of dollars and therefore net exporters to the U.S.

What this implies is that the U.S. must run persistent trade deficits with the rest of the world in order to provide the world with dollars.

This is not accurate. A current account deficit is not a net flow of dollars; it is a net flow of assets. We could pay for imports by selling real estate or equities or junk bonds. A foreign country could accumulate US dollar reserves (Treasuries) by selling assets like stocks or real estate or foreign government bonds.

The US current account deficit reflects the discrepancy between domestic saving and domestic investment. The US is not “forced” to run a deficit, even with the dollar serving as an international reserve currency.

I don’t worry about current account deficits, but if the Trump administration wishes to address the issue then they should consider reducing the government budget deficit (which is negative saving.) Instead, they are planning to enact a giant tax cut. A recession might also reduce the current account deficit, by reducing domestic investment.

PS. I’m not certain why Australia’s current account has recently become more positive; perhaps it reflects a cultural change associated with extensive immigration from (high saving) Asian nations. But that doesn’t explain Canada.