In my previous post, I took on the common claim that America is losing manufacturing jobs.

Not only are jobs growing, but job growth has outpaced population growth—i.e. the increase in the number of people available to fill those jobs—and this has been the case for most of the last four decades.

Is the fact that more people are working good news for the economy? As is often the case in economics, it depends. If real wages are rising and people want to work more in order to improve their standard of living, then sure, let’s celebrate the growth in productivity, output, and earnings. If wages are stagnant and some people would rather pursue non-labor vocations, but feel the need to earn a paycheck in order to keep up with the cost of living, then job growth would be at best a mixed bag.

At any rate, broadly speaking there are plenty of jobs out there to go around. As I like to remind my students, the most important skill required to get and keep a good job is something I probably can’t teach them in the classroom: a strong work ethic and a willingness to learn. If you know how to show up, listen, learn, apply yourself, and contribute to a production process, you’re not only going to be okay, you’re going to climb a ladder of employment success and growing wages as you gain skills and experience.

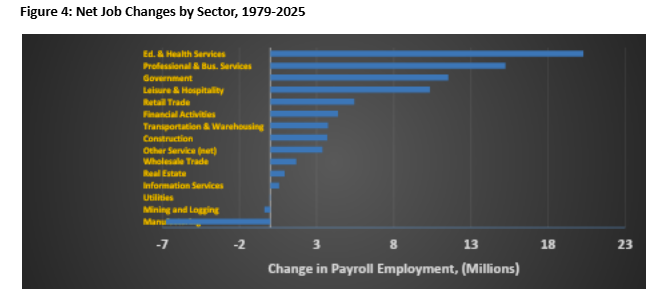

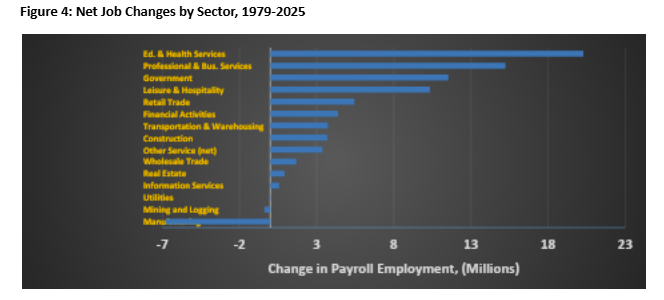

Yet despite the ever upward-trending job numbers, demagogues will contend that we’ve replaced good, high-paying manufacturing jobs with lousy service sector jobs. The service sector, broadly defined, has seen basically all of US employment growth, accounting for 90% of new jobs created since our 1979 benchmark, as shown in Figure 4. But beware making hasty assumptions about a sector that employs nearly 110 million people. When we compare earnings across different sectors of the economy, we see that a majority of the new service sector jobs pay better than manufacturing jobs, and most service sector jobs are safer and more pleasant than the factory jobs they’ve replaced.

Table 1 presents Bureau of Labor Statistics data on the 15 largest sectors and sub-sectors of the US economy, which together capture essentially all of the total net increase in payroll employment for the post-peak manufacturing jobs era (1979 to 2025). This might come as a surprise to the anti-globalization crowd: while we lost 7 million manufacturing jobs, and some mining, logging and utilities jobs, we’ve seen a net increase of nearly 69 million total jobs. Of these net new jobs, more than half of them (53.5%) feature average hourly earnings greater than current average hourly manufacturing earnings. Another 20% of new jobs have average hourly earnings within 10% of current manufacturing jobs. In other words, most of the 69 million new jobs pay better or close to the same wages than those “good” manufacturing jobs. So, we lost 7 million good jobs, only to gain about 37 million better-paying jobs, about 14 million close-paying jobs, and about 18 million lower-paying jobs (about 26% of net new jobs pay substantially less than manufacturing).

We’ve established that, despite a major decrease in employment in the manufacturing sector, we’ve gained many more jobs than we’ve lost in the past 45 years, and that most of these new jobs pay better. Economic changes, while painful in the short run, have brought gains in output and employment not only for the US, but for the rest of the world as well. Overall, this is good news for the US and world economies.

But even if we can get the protectionists to acknowledge that high-paying service sector jobs have more than replaced lost factory jobs, they’re still likely to whine that, “we don’t make things here anymore.” This complaint goes along with laments about the “deindustrialization” of America, implying that industrialization is over simply because the number of one particular kind of industrial job type (factory workers) is declining. This oft-heard refrain is patently false. We don’t make certain things, such as garments, toys or electronics, because global free trade and technological advances tend to shift America’s output into those industries in which our comparative advantage is greatest. But Americans do indeed make things, quite valuable things. This is nowhere more simply and obviously demonstrated than in the Industrial Production Index—a measure of the total US manufacturing output. As Figure 5 shows, after the expected steep decline following the Great Recession of 2008-2009, US manufacturing gradually recovered before getting walloped again during and after the Covid shutdowns. Still, this index, which consists mainly of manufacturing, has now recovered pre-Covid highs, and overall it’s grown by almost exactly 100% since the 1979 peak in manufacturing employment.

From an economic perspective, nothing could be better news. US manufacturing creates 100% more value with 35% fewer workers. Creating more value with fewer workers means we’re more efficient than ever, more productive than ever. These awesome productivity gains have many sources, especially in the form of technological advances in areas like software, robotics, and now the emergence of AI as the next great source of creative destruction. Globalization and outsourcing have also played a role, as they allow American workers a greater degree of specialization in those sectors where our productivity edge is largest. Regardless of the relative importance of technology vs. outsourcing in driving these changes, the broader point still stands: the US economy is both more productive and has more job opportunities than ever before.

Economists know that it’s at best useless and at worst scurrilous to talk of other countries “beating us” at trade, or of other countries having “unfair” advantages. I love to play football, but let’s face it: Jaylen Hurts is a better player than I (and 99.999% of the population). It’s not “unfair,” it just is. But it’s okay—I’m better at economics and writing than probably 98% of the population. So we each find our niche—he’ll throw touchdown passes and entertain millions, I’ll give lectures and write articles and teach hundreds about specialization, comparative advantage, and the always-present gains from trade. The entire economic system will have more of everything if each of us focuses on his or her comparative advantage and stops whining about things being unfair. As I like to instruct my students, “fairness” is a word not found in the economics lexicon, but we do like to use words like “wealth,” “growth,” and “prosperity.” The first lesson of market economics is that trade, on the basis of specialization, is a massively positive sum game. This is true for individuals, and it remains true when we aggregate the gains at a national scale. The thing is, since nobody can know in advance or from above what everyone else’s most productive specialization might be, we need a decentralized market process that gives us information and incentives, through price signals, that help each of us find our best opportunities and fit into the broader system in a more productive, more wealth-enhancing way. One of the main tasks for economists, especially we who teach the subject, is to explain not only how this system works, but to impress upon our students that the free market—unfettered by arbitrary and restrictive policies like tariffs—is the only way we can hope to achieve sustained gains from the division of labor.

They didn’t take “our” jobs. As long as we have even a semi-functional market economy, there will always be jobs to do. The real issue today is not creating jobs, but creating workers—people who are ready, willing, and able to show up, commit, and learn. So let’s stop the whining about “unfair” trade practices and the hectoring of other countries—especially our friends and allies—for “stealing” our jobs or “taking advantage of us” through trade that is necessarily mutually beneficial. Let’s instead count our blessings and make the best of a good situation. Teach people to have a good work ethic, and the rest will take care of itself.

Tyler Watts is a professor of economics and management at Ferris State University.

(0 COMMENTS)

Source link