Despite these similarities, their views diverged on fundamental issues. Smith argued that, besides leading to a better allocation of resources than alternative systems, free markets are compatible with a morally strong and cooperative society and, by implication, are not a menace to local customs. In contrast, Scruton believed that unfettered markets tend to erode traditional values and local cultural heritages. In his Dictionary of Political Thought, the entry on “conservatism” argues that defending limited government and private property does not necessarily imply a defense of capitalism (131-132). Moreover, he thought that “free trade is neither possible nor desirable. It is for each nation to establish the regulatory regime that will maximize trade with its neighbours, while protecting the local customs, moral ideals and privileged relations on which national identity depends” (A Political Philosophy, 32-33). In The Meaning of Conservatism, he concluded that “without the state’s surveillance, destitution and unemployment could result at any time” (112, 62, 150). Besides, he rejected liberalism for its atomistic focus; its separation of State and society, and its attempt “to speak for a universal human nature” (Ibid. 106).

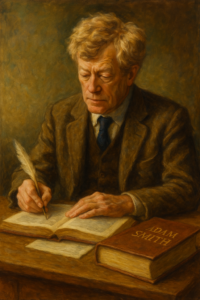

These theoretical differences complicate Scruton’s view of Smith as the theorist who “provided the philosophical insight that gave intellectual conservatism its first real start in life,” as he eventually held in Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition (2018, 27). The latter recognition marks a notable shift from his earlier neglect of Smith, which did not include Smith’s work either in the chapters or in the further suggestions. Scruton’s evolving view of Smith was explained a few years later in his Modern Philosophy: “Every now and then a thinker of the past is rediscovered as a great philosopher, and then makes the transition from the history of ideas to the history of philosophy. This happened recently with Adam Smith” (31). In light of Scruton’s evolving relationship with Smith’s ideas, I present his interpretation in a thematic and chronological order and a critical examination of his claims. The text is divided into three sections respectively entitled the human condition and the economy, the invisible hand, and morality and markets.

All in all, while Scruton developed a greater appreciation for Smith’s contributions over time, he did not fully understand or embrace his most fundamental concepts.

The Human Condition and the Economy

In A Short History of Modern Philosophy [1981] Scruton discusses the theory of moral sentiments in British philosophy, although he leaves out an analysis of Smith, whom he sees as merely continuing previous insights, concluding that he “produced no new system” (222-223). Therefore, the only substantive comment in regard to Smith’s thought is found in a chapter on Marx, in two paragraphs worth quoting at length:

- “The Wealth of Nations had summed up a century of liberal and empiricist thought by attempting to demonstrate that the free exchange and accumulation of private property under the guidance of self-interest not only preserves justice, but also promotes the social well-being as a whole (…).

- In order to establish that conclusion, Smith considers human nature to be something settled. The homo economicus of liberal theory is not thought of as a historical being. However, he is motivated by desires and satisfactions which, while represented as permanent features of the human condition, may in fact be no more than peculiarities of the eighteenth-century market economy” (212-213).

Two brief commentaries are warranted regarding these ideas. First, by downplaying Smith’s originality, Scruton went against the trend at the time, especially considering that Oxford University Press had already started publishing Smith’s complete works, sparking a renewed interest in his ideas. Secondly, Scruton correctly describes Smith’s take on economic dynamics, noting that free markets satisfy individual needs while promoting overall social prosperity. However, by confining Smith’s analytical framework to the specific characteristics of the eighteenth-century economy, he limits the broader applicability of Smith’s insights and diminishes their contemporary relevance. Scruton provides neither evidence nor a clear rationale for asserting that Smith’s descriptions were limited to the society of his time. In fact, the burden of proof falls on anyone who claims that homo economicus—the self-interested, desire-driven agent—is a concept confined to the past.

That said, Scruton may be onto something when he introduces the historical element in his analysis, since Smith recognized that economic institutions are dependent on historical and geographical factors. Whatever those forms may be, he still concluded that the “liberty, reason, and happiness of mankind (…) can flourish only where civil government is able to protect them” (WN 803).

“I believe that Scruton’s reading would have been enriched by recognizing that Smith’s account of the economic agent contains valid claims of universality while also acknowledging the historical and cultural variability of economic institutions.”

Therefore, I believe that Scruton’s reading would have been enriched by recognizing that Smith’s account of the economic agent contains valid claims of universality while also acknowledging the historical and cultural variability of economic institutions. In other words, from a Smithian perspective, while economic dispositions and dynamics transcend specific times and locations, economic systems develop along different paths shaped by their unique political and cultural contexts.

The Invisible Hand

In his Dictionary of Political Thought [1982], Scruton also included entries for “Adam Smith” and “Invisible Hand.” He concludes that, “Smith’s long-term influence on political thought, however, lies in his subtle development of the invisible hand conception of human society” (638-639). This conceptualization, however, requires clarification. Smith’s notion of the invisible hand is not a broad, general idea of human society; it specifically refers to the unintended benefits that arise from self-interested economic behavior. For example, when affluent consumers satisfy their material desires, they unintentionally contribute to the “distribution of the necessaries of life” to others, thereby aiding “the proliferation of the species” (TMS 184). Similarly, when businesspeople pursue the highest possible profits, they often, unintentionally, benefit society by increasing its annual revenue (WN 456). In both cases, the metaphor of the invisible hand explains how individual economic motivations can lead to positive unintended outcomes for society.

In extending the invisible hand to every aspect of social life, Scruton overlooks the fact that Smith’s approach to understanding human society goes far beyond material exchanges. His work encompasses morality, science, politics, fashion, literature, language, and religion—areas where the invisible hand concept does not apply. Smith presents a more complex and nuanced social analysis, where homo economicus is accompanied by natural sympathy and benevolence—dispositions that are also relevant for a flourishing society.

Another point that needs clarification is the assessment of beneficiaries in the market process. Scruton notes that the invisible hand does not “necessarily work to the benefit of the participants,” as there are instances, like the “prisoners dilemma,” where individuals may thwart their own goals (345). However, it seems problematic to use the example of two suspects under police arrest, in a fearful and confined situation, as a representative sample of market interactions. In any case, the key issue is not whether market participants are perfectly rational, but rather what alternative we use as a basis for comparison. Smith’s argument is that “the system of natural liberty” (WN 687) consistently proves more beneficial when compared to other systems, such as mercantilism, provided that certain conditions are in place.

Chief among these conditions is the government’s role in protecting individuals by ensuring security against harm and administering justice fairly (TMS 340-341; WN 687, 708). Examples of market exchanges that fail to benefit economic agents often involve instances where self-interest violates the rules of justice—such as when producers seek special privileges driven by “the wretched spirit of monopoly” (WN 461) or when a “few individuals […] endanger the security of the whole society” (WN 324).

In Political Philosophy [2006], Scruton himself acknowledges that “the ‘invisible hand’ depends upon, and is secretly guided by, a legal and institutional framework” (18). However, it is unclear why he refers to these frameworks as “secret guides,” since in Smith’s account they are intentional, explicit, and publicly known structures that ensure just and orderly interactions. Additionally, in areas such as public works and basic education, institutions must be established and managed through deliberate political decisions. This ‘visible’ hand of government, however, does not extend to passing laws for the protection of “the social well-being of the workforce,” as Scruton argues (2018, 30). Although Smith expressed concern about the mental conditions of workers, he did not call for welfare laws to directly address these issues.

In any case, Scruton is right to recognize that the invisible hand process “is a distillation of social knowledge, enabling each participant in the market to respond to the desires and needs of every other” (2018, 28-30). This epistemic function of free markets is perhaps one of Smith’s most important contributions.

Morality and markets

In How to Be a Conservative [2014], Scruton writes that, for Smith, markets work properly “only where there is trust between its participants (…) it is where sympathy, duty, and virtue achieve their proper place that self-interest leads, by an invisible hand, to a result that benefits everyone” (28). This passage raises an inevitable question when approaching Smith’s works: how do markets relate to issues of trust, sympathy, duty, and virtue?

For Smith, markets function primarily on the basis of individual material self-interest: we persuade others “that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them… [we] never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages” (WN 26-27). The moral qualities required to engage successfully in market dynamics propelled by self-interest include “industry, discretion, attention, and application of thought” (WN 304-305). Therefore, Scruton misinterprets Smith when he asserts that in a market economy “free exchanges take place under the eye of conscience – Smith’s impartial spectator” (74). Economic exchanges do not depend on the impartial spectator establishing degrees of sympathy, duty, and virtue; rather, they rely on the unconditional respect for the “rules of a fair game” (TMS 83; WN 687), regardless of whether conscience mandates it. Markets depend on trust in the system of justice, and trust arises from repeated interactions among individuals within a stable and predictable framework. It is justice that generates trust, not the other way around. Thus, merchants seek trustworthy exchanges and laws that protect them (WN 454). In this regard, Scruton correctly notes that for Smith, justice as a negative virtue is “the essential foundation of a well-ordered society” (2018, 27).

In sum, the impartial spectator, contrary to what John Rawls thought, does not assess social systems, nor does it dictate economic actions, as Scruton believes. Its role is confined to evaluating the propriety of individual moral actions. This does not imply that economic exchanges are amoral; as noted earlier, Smith acknowledges the moral aspects of economic behavior. However, these actions are driven by individuals’ capacity to fulfill each other’s interests, rather than by direct moral considerations.

By asserting that moral considerations must intervene in and define market outcomes, Scruton seems to endorse what Smith calls the moralist’s complaint that “wealth and greatness are often regarded with the respect and admiration which are due only to wisdom and virtue” (TMS 61-62). Again, wisdom and virtue undoubtedly have intrinsic value and are noble, praiseworthy qualities, but they do not govern the market. Indeed, while Smith critiques the “luxury and caprice,” “selfishness and rapacity,” and “vain and insatiable desires” fostered by the unchecked pursuit of wealth and power (TMS 184), he nevertheless believed that individuals should be free to pursue such excesses. In doing so, he argued, they would unintentionally benefit others throughout the process of satisfying their self-interest.

Conclusion

Roger Scruton grew increasingly sympathetic to Smith’s ideas over time. While in 1981 he found little originality in Smith’s work and confined his assumptions to eighteenth-century society, by 2018 he regarded Smith as the first important conservative intellectual and acknowledged his unique contribution to understanding free social orders. This shift is unsurprising, as Smith’s theory can be well integrated into the conservative defense of local cultures, social practices, traditions, and the norms and institutions that protect them.

That said, conservatism may support state intervention to prevent social change, distrust abstract theories and general principles, defend forms of economic protectionism, and exhibit a “nationalistic bias,” as Friedrich Hayek pointed out in The Constitution of Liberty (519-527). In contrast, classical liberals embrace change if it promotes individual freedom, believe that government should play a more limited role in economic and social life, support general principles, and tend to downplay nationalistic concerns. From this perspective, Smith aligns more closely with classical liberalism than with full-fledged conservatism.

For more on these topics, see

Although Scruton supported some of Smith’s classical liberal ideas, he remained fundamentally a conservative. This position led him to criticize the liberal emphasis on individualism and to qualify his defense of markets by prioritizing national identity over the more liberal view of global economic orders. Indeed, Scruton’s conservative perspective shaped his interpretation of Smith’s key concepts. He saw the invisible hand as a broad conception of society, argued that global free trade was neither possible nor desirable, and believed that a strong sense of morality should limit markets. These views diverge from Smith’s, who used the invisible hand strictly as an economic metaphor, saw free trade as both conceptually possible and desirable, and argued that markets should be constrained mostly by the rules of negative justice.

References

F.A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty. University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought. Harper and Row, 1983.

Roger Scruton, A Political Philosophy: Arguments for Conservatism. Bloomsbury, 2019.

Roger Scruton, Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition. All Points Books, 2018.

Roger Scruton, How to be a Conservative. Bloomsbury, 2015.

Roger Scruton, The Meaning of Conservatism. St. Augustine’s Press, 1980.

Roger Scruton, Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey. Bloomsbury, 2012.

*Alejandra M. Salinas is a Professor at UNTREF and UCA in Buenos Aires, whose focus is on contemporary political philosophy, comparative political theory, social theory, democratic institutions and literature and politics.

For more articles by Alejandra Salinas, see the Archive.