There is something that, I think, libertarians have learned, or should be learning, from the current American administration about the rule of law. One illustration among many was provided on March 13 when Ursula von der Leyen announced the European Union’s response to Trump’s 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports. (See “EU and Canada Retaliate after Donald Trump’s Metals Tariffs Take Effect,” Financial Times, March 12, 2025, which includes a short video of von der Leyen’s announcement.) As the president of the European Commission, the deep-state arm of the EU government, she spoke in a calm voice, emphasized that the European retaliatory tariffs were proportionate to Trump’s, and that the trade war started by the latter was “bad for business, and even worse for consumers.” The European tariffs needed to be approved within the EU and would come into force on April 13. Although the real solution for consumers would be unilateral free trade, contrast this reaction with the excited, erratic, one-man, pouting announcement on the American side. But there is more to that than one small example.

I take the rule of law to be the ideal defended by the classical liberal tradition and notably by Friedrich Hayek. It is made of “rules regulating the conduct of persons towards others, applicable to an unknown number of future instances and containing prohibitions delimiting (but of course not specifying) the boundaries of the protected domain of all persons and organized groups,” including equally government agents (see his Law, Legislation, and Liberty, p. 457 and passim). It is the ideal of a government of laws, not men.

We are re-learning that the rule of law provides an essential protection to individual liberty and thus prosperity—at least until a liberal or capitalist anarchy is attained, if this moment ever comes. The demise of the rule of law is much more likely to lead to arbitrary power, which has been the definition of tyranny in the classical liberal tradition.

This lesson is probably more important for Americans than for Europeans because the American Revolution was unusually successful and may suggest that the rule of law can easily be re-engineered if it breaks down. With few exceptions in Europe, it repeatedly broke down in recent times: in the last three-quarters of a century, many countries have been ruled by autocracies, not counting the 1789 cataclysm of the French Revolution. Each time, the rule of law was reestablished with great difficulty and arguably only in part. The establishment of the European Union was partly meant to solidify the rule of law, notwithstanding that it is often over-restrictive and over-bureaucratized. Yet, it can be argued that the EU has protected the residents of its member countries from overt forms of tyranny for several decades.

It was generally believed that the rule of law was much stronger in America than in other countries. Today, it is arguably in America that the rule of law is most threatened. Many Americans don’t see this or falsely imagine that the path to tyranny closes when a strongman of their own flavor is in power. Despotism can happen here.

Even imperfect (but not a mere smokescreen of law), the rule of law is still preferable to open arbitrariness, with two qualifications. First, the rule of law should tolerate a certain measure of principled civil disobedience, but from the ruled, not from the rulers. Secondly, a revolution is justified to the extent that it is necessary to abolish a tyrannical government and replace it with the rule of law, not to replace an arbitrary regime with another.

How can the rule of law be preserved? One necessary condition has been universally recognized by the classical liberal tradition and the economic analysis of institutions: the independence and irremovability of judges. Up to some supreme court, a judicial ruling or order can be appealed, but until then, one judge can stop the wheels of the armed and powerful state. (See Bertrand de Jouvenel’s On Power.)

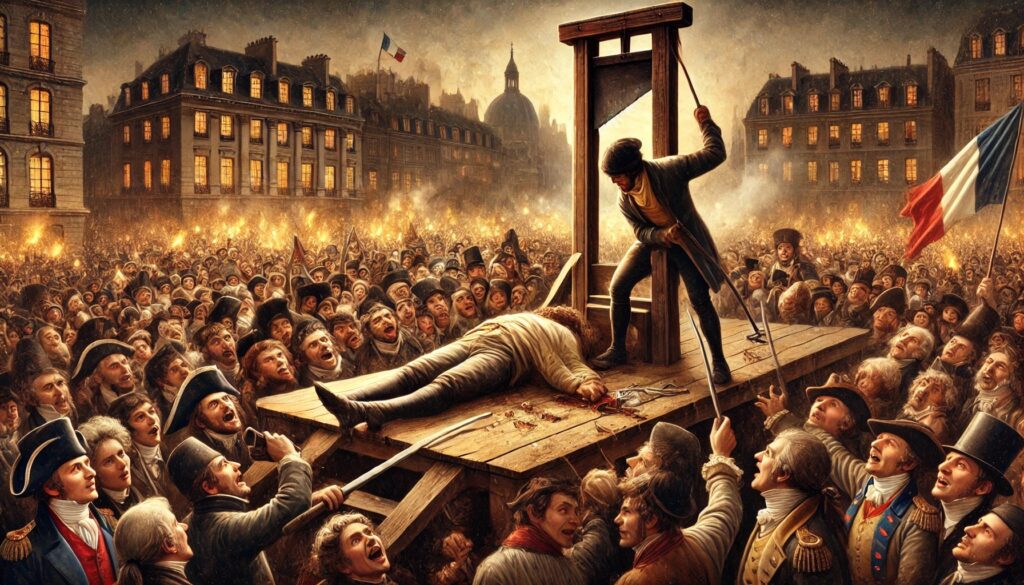

This is a crucial requirement, notwithstanding a White House deputy press secretary proclaiming that “rogue judges are subverting the will of the American people.” It’s a reasonable bet that she has never read Jean-Jacques Rosseau and does not know what she is talking about, but she gives us an idea of the atmosphere she breathes. If or when the “will of the people,” which a few of the higher-ups in the administration have also invoked against independent courts, turns against any of them, one judge could stand between him and “the people.” Historical examples are legion. If there had been independent courts, Maximilien Robespierre, a previously popular revolutionary leader against whom the mob was now clamoring, could have appealed to a judge before he was guillotined in Paris on July 28, 1794.

******************************

“Robespierre guillotined,” by DALL-E (with numerous historical and technical incongruities)