During his lifetime, the social and political writings of Thomas Merton caused a ruckus in the Catholic Church and in public opinion at large. No Catholic theologian, and especially not a monk, was supposed to be as explicit as Merton was in his denunciation of racism and his support of the social rights movement, so fierce against the Cold War, the Vietnam war and the atomic bomb, and so strongly in favor of regulations of industry for the sake of the environment — which was quite a new thing even in his later years.

His flirting with Marxism — as quite ignorant or disingenuous people would have it — was seen as especially problematic, giving Merton’s influence especially over conscious Catholic laity, as well as monks, nuns, and priests. The possibility that his death should be listed as one of the egregious political assassinations of the late 1960s appears to be high.

In his book A Way to God, Matthew comments, after reviewing the evidence: Perhaps we will never know whether or not Merton died as a martyr at the hands of the American government. But it is very possible he did. I believe he did.

It is easy to recognize Merton’s via transformativa not only because his social engagement was so obvious, but because it was for him an integral part of his vocation as a Christian and a human being. As Matthew points out, Merton knew the prophetic tradition very well. In fact, he once wrote a letter to a rabbi saying that he often sat on his front porch in his hermitage and shouted the poetry of Isaiah and others into the air about him.

He was aware of the need for both an inner and an outer dimension of the faith. He wrote: “How are we going to affirm to the modern world the scandal of the New Testament? It is here that we confront the seriousness of our prophetic as distinct from our contemplative calling.”

I would argue that here we find already the core couple of mysticism-prophetism from which Matthew Foxwould later develop the four viae: mysticism divided into sunny (via positiva) and dark (via negativa), and prophetism divided into personal (via creativa)

and political (via transformativa), thus reaching a kind of archetypal completion.

For Merton, in his time and age, and for the people around him, adding the fight for social justice to the contemplative calling of the monk was, however, a big deal. It was still an issue, decades later, for Matthew, who had to confront the listless and sentimental understanding of spirituality put foward by Ratzinger and his cronies. As we know, he answered the question “mysticism or prophecy?” with a both/and, not an either/or, and Merton eventually did the same. There is no doubt that Merton today would be on the forefront of the protest against the treatment of Palestinians and would denounce loudly the travesty of Judaism performed by the government of the state of Israel. And he would do so in the name of Jewish values.

Perhaps a specific trait of Merton’s engagement with the via transformativa is represented by underlining its deep connection with the via creativa: the artist in him is a prophet, and the prophet expresses himself in artistic forms, just as he praised writers and artists of the recent past for their prophetic role, that is, for their ability to see within society both the cracks and the buddings

that others could not yet see.

This is not dissimilar, in fact, from Matthew’s own notion, which he expounds in one of his early books: The poets, the painters, the musicians, the scriptwriter — those are frequently those who lead the struggle with the demons of life in our day.

Listen to Merton addressing an audience of monastics on the last day of his life: “Are monks and hippies and poets relevant? No, we are deliberately irrelevant. We live with an ingrained irrelevance which is proper to every human being. The marginal man accepts the basic irrelevance of the human condition, an irrelevance which is manifested above all by the fact of death. The marginal person, the monk, the displaced person, the prisoner, all these people live in the presence of death, which calls into question the meaning of life.”

Taking up Merton’s writings today, and doing so with the four paths as an hermeneutical tool, is undoubtedly very enlightening. It is especially complex, however, when it comes to the via transformativa because much of the social and technological contexts have changed, while so many of the problems of his time, instead of going away, have simply grown to monstrous proportions.

Racism, political corruption, ecological destruction, and cynicism have reached a level which Merton could hardly imagine. What would he do?

See Matthew Fox, A Way to God: Thomas Merton’s Creation Spirituality Journey, pp. 107, 132, 142.

See also Fox, Prayer: A Radical Response to Life, p. 140.

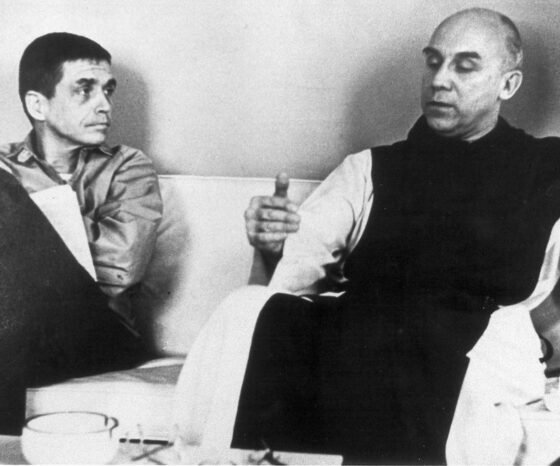

Banner image: “Thomas Merton & Dan Berrigan” — two men of the cloth, both courageous activists. Photo by Jim Forest, November 1964. Flickr.

Queries for Contemplation

How do I address the issue of my own irrelevance in the face of genocide? What does Merton mean by “deliberate irrelevance”?

A Way to God: Thomas Merton’s Creation Spirituality Journey

In A Way to God, Fox explores Merton’s pioneering work in interfaith, his essential teachings on mixing contemplation and action, and how the vision of Meister Eckhart profoundly influenced Merton in what Fox calls his Creation Spirituality journey.

“This wise and marvelous book will profoundly inspire all those who love Merton and want to know him more deeply.” — Andrew Harvey, author of The Hope: A Guide to Sacred Activism

Prayer: A Radical Response to Life

How do prayer and mysticism relate to the struggle for social and ecological justice? Fox defines prayer as a radical response to life that includes our “Yes” to life (mysticism) and our “No” to forces that combat life (prophecy). How do we define adult prayer? And how—if at all—do prayer and mysticism relate to the struggle for social and ecological justice? One of Matthew Fox’s earliest books, originally published under the title On Becoming a Musical, Mystical Bear: Spirituality American Style, Prayer introduces a mystical/prophetic spirituality and a mature conception of how to pray. Called a “classic” when it first appeared, it lays out the difference between the creation spirituality tradition and the fall/redemption tradition that has so dominated Western theology since Augustine. A practical and theoretical book, it lays the groundwork for Fox’s later works.

“One of the finest books I have read on contemporary spirituality.” – Rabbi Sholom A. Singer