Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell, Professor of Economics at the University of Houston, Sebin Nidhiri and Swati Singh, Ph.D. students at the University of Houston.

The Federal Reserve Board started a strategy review at the beginning of 2025 which it intends to complete by late summer. After its only previous review, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) adopted a far-reaching Revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy in August 2020. The framework contains two major changes from the original 2012 statement. First, policy decisions will attempt to mitigate shortfalls, rather than deviations, of employment from its maximum level. Second, the FOMC will implement Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) where, “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

The 2019 review was heavily influenced by economic performance over the previous decade, including the Effective Lower Bound (ELB) period from December 2008 – December 2015 and the difficulty in raising inflation to the Fed’s 2 percent target. While it was reasonable to assume in 2019 that the issues over the previous decade would continue, the 2025 review will be more difficult because, hopefully, the next five years will not involve a repetition of the Covid-19 recession, recovery, inflation, and disinflation. Powell (2025) has recently made it clear that the FOMC is reconsidering the language about both shortfalls and FAIT.

This post is based on our paper, Policy Rule Evaluation for the Fed’s Strategy Review,

where we analyze policy rules that are either in accord with the original statement or inspired by the revised statement and use the rules to evaluate monetary policy using the Linearized Version (LINVER) of the Federal Reserve Board/United States (FRB/US) model.

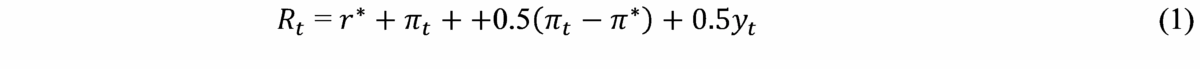

The Taylor (1993) rule is as follows,

where Rt is the level of the short-term federal funds interest rate prescribed by the rule, πt is the annual inflation rate, π* is the 2 percent target level of inflation, yt is the output gap, the percentage deviation of GDP from potential GDP, and r* is the neutral real interest rate that is consistent with inflation equal to the target level of inflation and GDP is equal to potential GDP in the longer run. When inflation equals its 2 percent target and GDP equals potential GDP, the federal funds rate equals the neutral real interest rate plus the 2 percent inflation target.

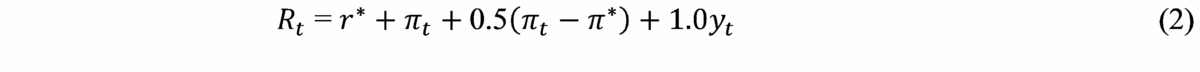

Taylor (1999) and Yellen (2012) analyzed an alternative to the Taylor rule that is called the balanced approach rule, where the coefficient on the inflation gap is 0.5 but the coefficient on the output gap is raised to 1.0. The balanced approach rule is

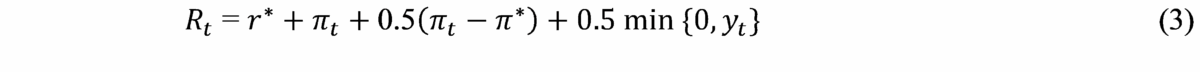

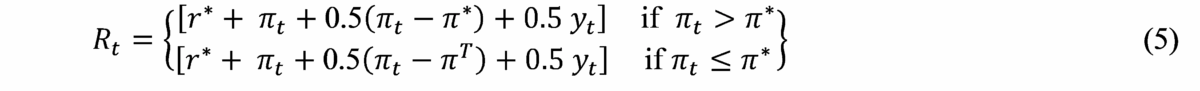

The Taylor (shortfalls) rule mitigates employment shortfalls instead of deviations by having the FFR only respond to unemployment if it exceeds longer-run unemployment. The version with the output gap is,

If the output gap is negative, the FFR prescriptions are the same as with the Taylor rule. If the output gap is positive, the FOMC will not raise the FFR solely because of low unemployment. The balanced approach (shortfalls) rule is the same as the Taylor (shortfalls) rule except that the coefficient on the output gap equals 1.0 instead of 0.5. Shortfalls rules were discussed in the March 2025 FOMC meeting.

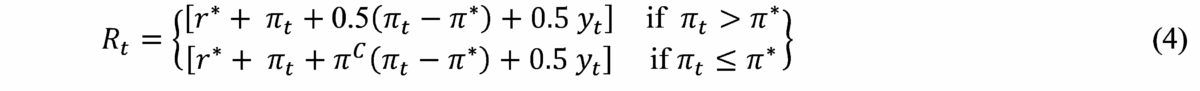

We propose two new types of rules inspired by the revised statement. The first is the Asymmetric Coefficient Inflation Targeting (ACIT) rule where the coefficient on the inflation gap is larger when inflation is below 2 percent. The ACIT Taylor rule is

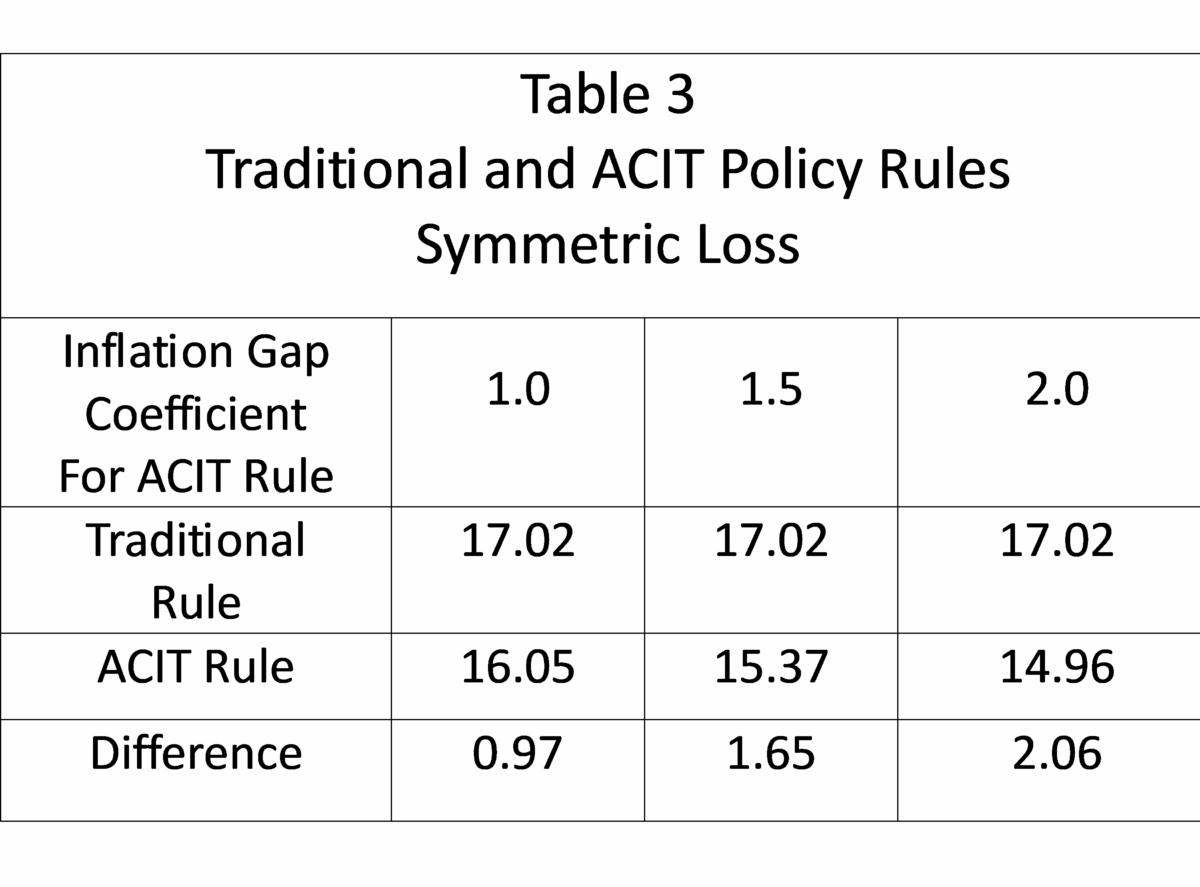

We analyze rules where the coefficient on the inflation gap when is 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0. When inflation exceeds the 2 percent inflation target, the rule is identical to the Taylor rule. When inflation is less than the 2 percent inflation target, the rule provides more stimulus than the Taylor rule. The balanced approach rule version is identical to the Taylor rule version except that the coefficient on the output gap is 1.0 instead of 0.5. The ACIT rule provides more stimulus than the traditional rules when inflation is below 2 percent and the same amount of restraint when inflation is above 2 percent. Once inflation exceeds 2 percent, policy acts to reduce inflation to, but not below, the 2 percent target.

The second proposed type of rule is the Asymmetric Target Inflation Targeting (ATIT) rule where the inflation target is larger than 2 percent when inflation is below 2 percent. The ATIT Taylor rule is

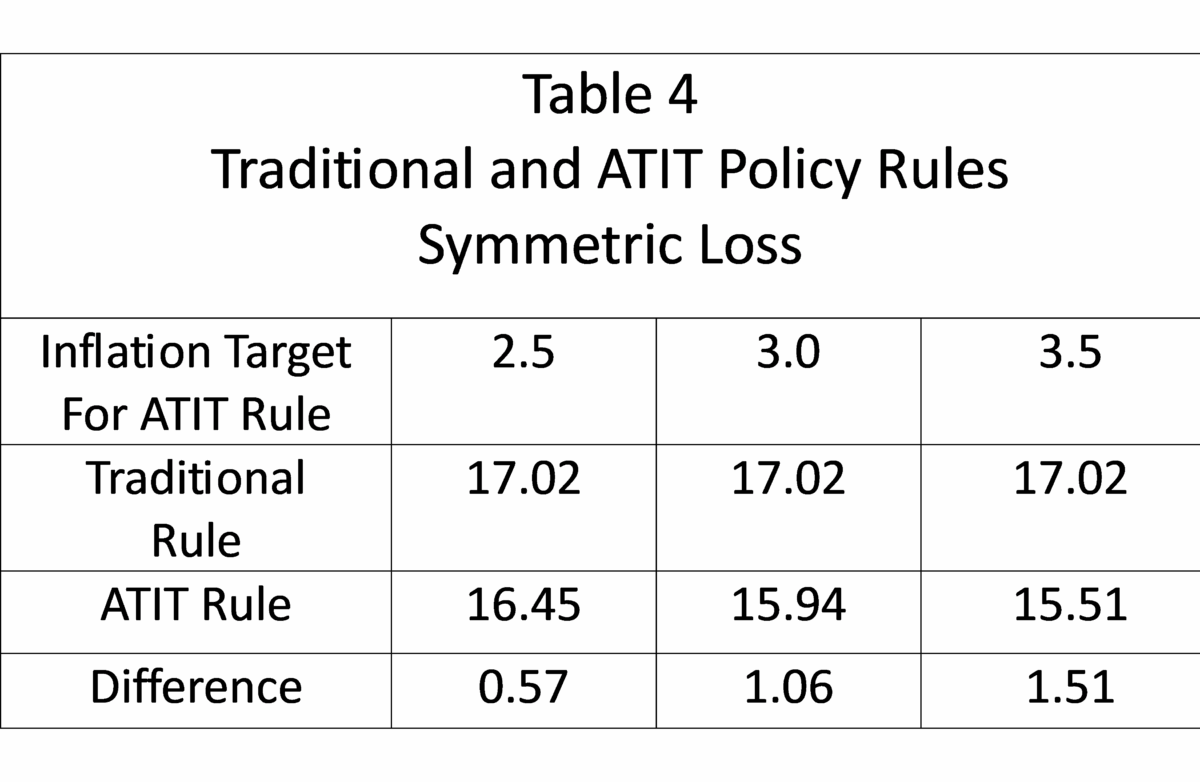

We analyze rules when the inflation target when is 2.5, 3.0, and 4.0. When inflation exceeds the 2 percent inflation target, the rule is identical to the Taylor rule. When inflation is less than the 2 percent inflation target, the rule provides more stimulus than the Taylor rule. The balanced approach rule version is identical to the Taylor rule version except that the coefficient on the output gap is 1.0 instead of 0.5. Similar to the ACIT rules, the ATIT rules provides more stimulus than the traditional rules when inflation is below 2 percent and the same amount of restraint when inflation is above 2 percent. Once inflation exceeds 2 percent, policy acts to reduce inflation to, but not below, the 2 percent target.

Clarida (2022) identifies time consistency and asymmetry as two characteristics of FAIT. The ACIT and ATIT rules are time consistent. When inflation rises above 2 percent, the coefficient on the inflation gap in the ACIT rule and the inflation target in the ATIT rule immediately revert to their values in the traditional rules. There is no conflict between the FOMC’s actions and objectives. The rules are also asymmetric. Once inflation rises above 2 percent and the ACIT and ATIT rules revert to the traditional rules, policy immediately switches from stimulus to restraint.

As inflation falls towards the 2 percent target, the amount of restraint becomes smaller with a goal of returning inflation to its 2 percent target, but not below.

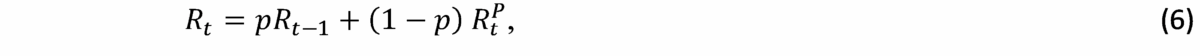

These rules are non-inertial because the FFR fully adjusts whenever the target FFR changes. This is not in accord with FOMC practice to smooth rate increases when inflation rises. We specify inertial versions of the rules based on Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999),

where is the degree of inertia and is the target level of the federal funds rate prescribed by Equations (1) to (5). We set as in Bernanke, Kiley, and Roberts (2019). is the prescription from (6) in the previous period. To implement a zero lower bound, a constraint is imposed that the target rate is set to zero if the prescribed rate is negative.

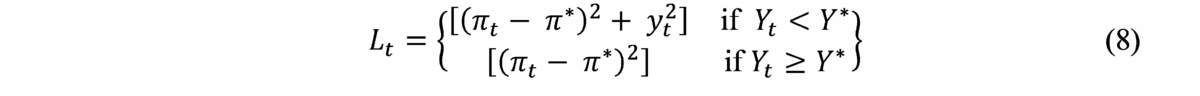

The standard method to evaluate economic performance, as in Taylor (1979), is with a quadratic loss function where the goal of policy is to minimize the sum of squared inflation loss and squared output loss where is inflation, is the inflation target, and is the output gap.

This is a symmetric loss function where, in accord with the FOMC’s dual mandate, inflation loss and output loss are equally weighted.

Starting in July 2016, a shortfalls loss function has also been reported in the Tealbook,

where output loss is equal to the squared output gap if GDP is below potential GDP and zero if GDP is above potential GDP. The motivation comes from a “flat” Phillips curve where GDP above potential or unemployment below longer-run unemployment has weak effects on subsequent inflation. The shortfalls loss function both predates and embodies the part of the revised statement replacing deviations with shortfalls from maximum employment.

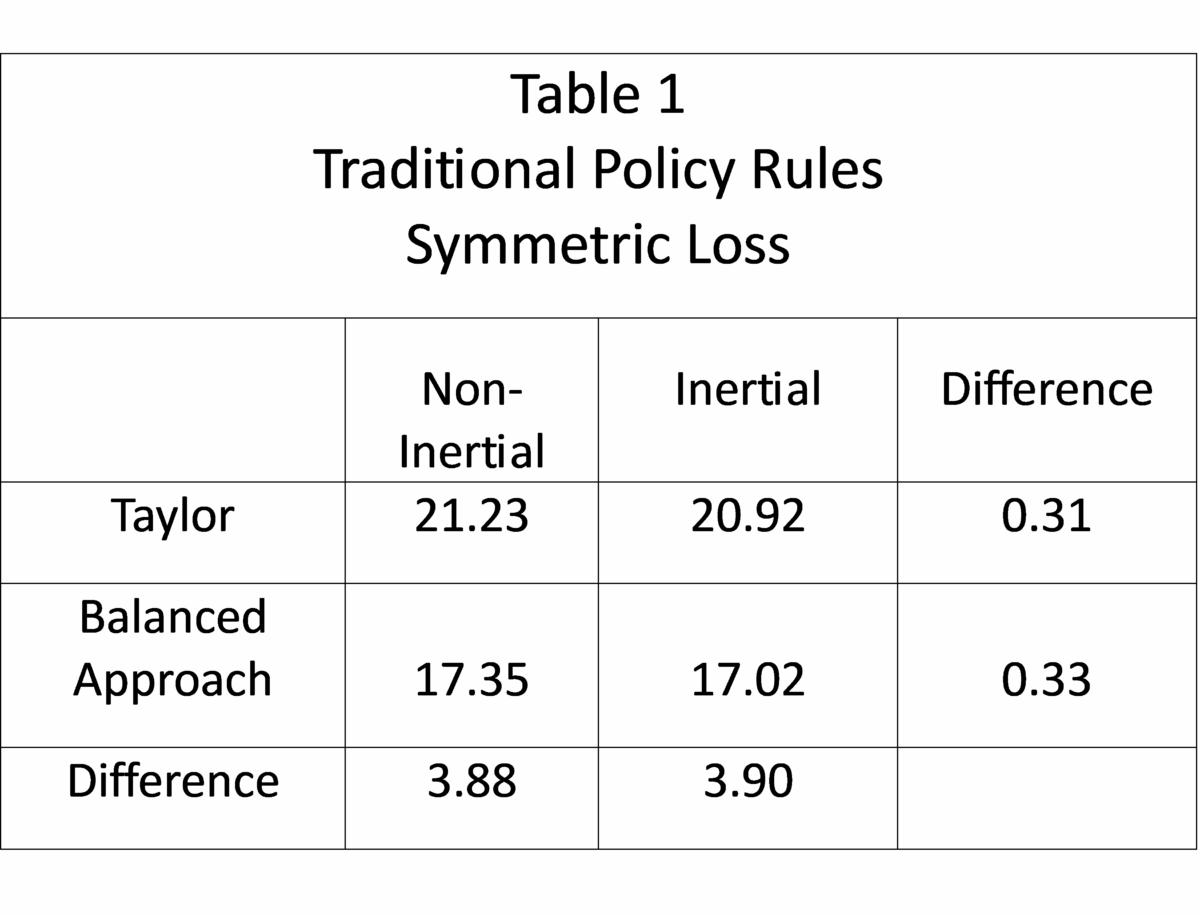

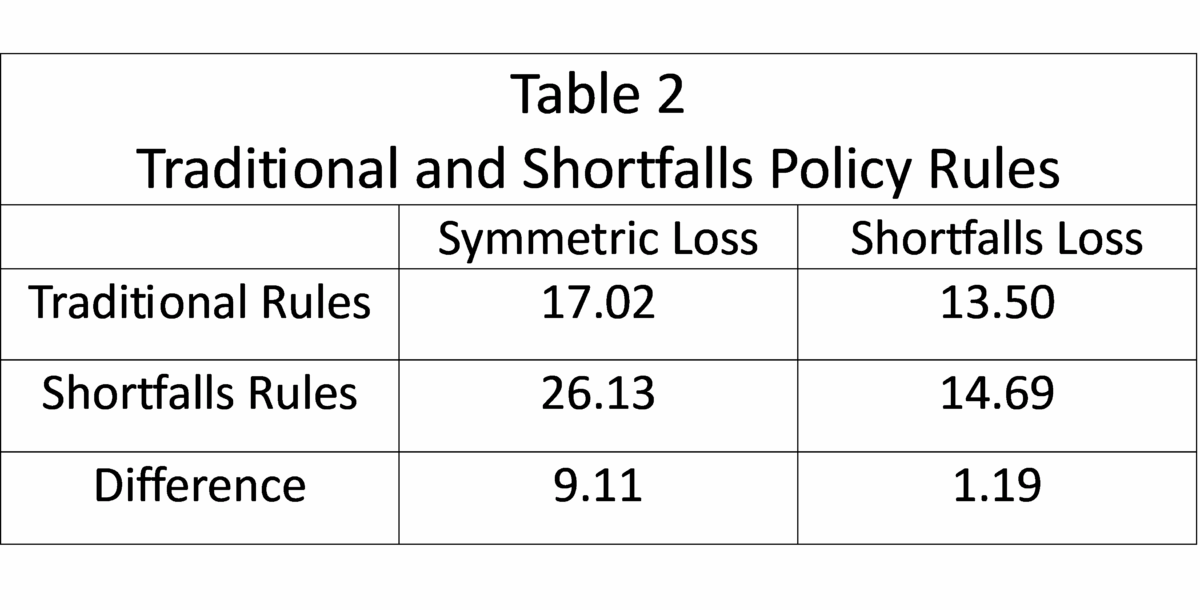

Table 1 evaluates traditional policy rules with symmetric loss. Economic performance is better with balanced approach rules than with Taylor rules, as the loss is smaller with balanced approach rules for both non-inertial and inertial specifications. Economic performance is marginally better with inertial than with non-inertial rules as the loss differences are small. Table 2 evaluates traditional and shortfalls inertial balanced approach rules. Traditional rules perform better than shortfalls rules, with the differences much larger with symmetric than with shortfalls loss. Tables 3 and 4 evaluate traditional and either ACIT or ATIT inertial balanced approach rules. Economic performance is better with ACIT and ATIT rules than with traditional rules and improves with either larger inflation gap coefficients for the ACIT rule or larger inflation targets for the ATIT rule. The differences are larger than between non-inertial and inertial rules and smaller than between Taylor and balanced approach rules.

Much of the discussion surrounding the 2025 Strategy Review has advocated abandoning FAIT and returning to essentially the 2012 framework. Our research shows that it is possible to design policy rules that are asymmetric, time consistent, in accord with FAIT and outperform traditional rules.

This post written by David Papell, Sebin Nidhiri and Swati Singh.